- Home

- Lucius Shepard

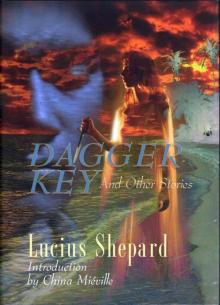

Dagger Key and Other Stories

Dagger Key and Other Stories Read online

Lucius Shepard is a grand master of dark fantasy, famed for his baroque yet utterly contemporary visions of existential subversion and hallucinatory collapse. In Dagger Key, his fifth major story collection, Shepard confronts hard-bitten loners and self-deceiving operators with the shadowy emptiness within themselves and the insinuating darkness without, to ends sardonic and terrifying. The stories in this book, including six novellas (one original to this volume) are:

“Stars Seen Through Stone”—in a small Pennsylvania town, mediocrity suddenly blossoms into genius; but at what terrible cost?

“Emerald Street Expansions”—in near-future Seattle, echoes of the life of a medieval French poet hint at cither reincarnation or a dire conspiracy.

“Limbo”—a retired criminal on the run from the Mafia encounters ghosts, and much worse, on the shores of a haunted lake.

“Liar’s House”—in the grip of the legendary dragon Griaule, destiny, is a treacherous and transformative thing.

“Dead Money”—a small-time New Orleans criminal ventures outside his proper territory, and poker and voudoun conspire to bring him down.

“Dinner at Baldassaro’s”—a gang of immortals debates the future in an Italian resort, only for events to outrun any of their expectations.

“Abimagique”—a glib college loser falls in love with a witch, becoming an involuntary part of a world-saving—or world-destroying—magical ritual.

“The Lepidopterist”—a small boy on a Caribbean island witnesses the creation of preternatural beings by a Yankee wizard…

“Dagger Key”—off the coast of Belize, the ghost of a famous pirate seems to control a spiral of murder and intrigue; or is someone else responsible?

Dagger Key And Other Stories / Copyright © 2007 by Lucius Shepard

Introduction / Copyright © 2007 by China Miéville

Cover / Copyright © 2007 by J.K. Potter

Published in September 2007 by PS Publishing Ltd. by arrangement with the author. All rights reserved by the author.

FIRST EDITION

ISBN

978-1-904619-74-1 (Deluxe slipcased hardcover)

978-1-904619-73-4 (Trade hardcover)

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places and incidents either are products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events or locales or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

“Stars Seen Through Stone” first appeared in The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, July 2007; “Emerald Street Expansions” first appeared on Sci Fiction, March 2002; “Limbo” first appeared in The Dark, edited by Ellen Datlow (Tor, 2003), and has been revised for its appearance here; “Liar’s House” first appeared on Sci Fiction, December 2003; “Dead Money” first appeared in Asimov’s, April 2007; “Dinner at Baldassaro’s” first appeared in Postscripts 10, Spring 2007; “Abimagique” first appeared on Sci Fiction, August 2005, and has been extensively revised for its appearance here; “The Lepidopterist” first appeared in Salon Fantastique, edited by Ellen Datlow and Terry Windling (Thunder’s Mouth, 2006); “Dagger Key” is original to this collection.

Design and layout by Alligator Tree Graphics

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Biddles Ltd

PS Publishing Ltd / Grosvenor House / 1 New Road / Hornsea, HU18 1PG / Great Britain

e-mail: [email protected] • Internet: http://www.pspublishing.co.uk

CONTENTS

Introduction by China Miéville

Stars Seen Through Stone

Emerald Street Expansions

Limbo

Liar’s House

Dead Money

Dinner At Baldassaro’s

Abimagique

The Lepidopterist

Dagger Key

Story Notes

INTRODUCTION

Griaule and the Mountains

(warning—spoilers ho.)

Lovers of the fantastic are special.

We, and especially we, can see through the grubbiness of reality. We, and especially or even only we, are attuned to the marvellous, not bowed down by the grinding tedium of quotidian life. It’s no wonder we so love the figure of the special, visionary child who never fits in with her so-boring parents, town and classmates, and who eventually finds her way to the enchanted land she deserves. We are that child. In our passion for the magic behind the everyday, we are an elect.

Yeah.

Right.

Is that a parody of the position? Certainly, a little, but consider the cavalierly nouned adjective “Mundane”. It’s a common enough term used by some SF/F fans to refer to those who prefer their cultural production “realist” and mainstream. Such an epithet bespeaks the ludicrously aggrandising self-image of some fans of the fantastic. Because if they, everyone else, are “mundane”, what are we, but, well…special?

Fortunately there have always been countertraditions. There are, for example, the anti-fantasies of M. John Harrison, or Michael Swanwick’s astonishing The Iron Dragon’s Daughter. These are books with an antagonistic, even punitive relationship with the fantastic they express.

And there’s Lucius Shepard.

Shepard, too, is too tough, too political to let fantasy believe in its own fey daydream of escape. But his strategy is not one of scorching earth. It is a little gentler, no less effective, and altogether fascinating.

It’s hard to put your finger on. You read and reread these stories, and know that something strange is going on, but for a while you can’t work out what it is.

At last it hits you. In the stories of Dagger Key, Lucius Shepard makes the fantastic a bit low-key.

Wait, wait. There’s no cause for alarm. This is high praise, not criticism. This is at the crux of what makes Shepard so exceptional.

Let’s be clear: addicts of the wow-porn we call the Sense of Wonder need not be concerned—Dagger Key contains unspeakably alien creatures, body-hopping ghosts, impossible conspiracies, zombies (a rare treat, “Dead Money”, a follow-on to the astonishing early novel Green Eyes), fallen angels, dimensional portals, lives after deaths, a sex-magic apocalypse, and a story set on and around the flanks of what is perhaps Shepard’s most popular and enduring creation, the huge, nebulously malevolent dragon Griaule.

But despite and alongside the traditional vasty strangeness of these concerns, Shepard brilliantly and provocatively pokes the grandiosity of the strange, in his precise delivery, his bewildered protagonists, his refusal of bombastic catharsis or explanation. He teases the magic.

Take the book’s opening story, “Stars Seen through Stone”. It opens with Shepard’s usual exceptionally acute dialogue and observations, a study of a loathsome little man. Gradually the scene becomes more uncomfortable, at first in ways that would be familiar in “mainstream” fiction, before the gradual realisation that something else is going on. Some entity from beyond is spreading its influence. It is preparing to feed. The wall between worlds is growing thin. Until, at last, in a vivid and dramatic supernatural culmination, those boundaries are breached, and things from beyond emerge, to feast, to harvest humans.

After which, we learn, “there was a hue and cry about leaving the town, [until]…calmer voices prevailed, pointing to the fact that there had been no fatalities”.

Wait…what?

It’s a horror story. What else can it be? That burgeoning foreboding, the creaking of the seams of the world, the maleficent intervention, the breach, the monstrous feeding. But how many horror stories end, in effect, “…and then everything was back to normal and no one died”?

The events described weren’t the apocalypse they appeared to be. They were just something that happened, and t

hat finished without that much lasting impact. It is an absolutely bravura move, that only a writer of supreme confidence and guts could carry off.

Shepard knows well that we have read the same books he has. He knows that we know how that story must end. He withholds, though, because that is not the universe in which his characters live. We may have thought they lived in a story, but actually they are somewhere more real, more natural than that.

That is the key. The signs are there: Shepard’s dialogue; his descriptions of landscape; his focus on human motivations; his political savvy. He is a naturalist (in a particularly American tradition). All the dragons, zombies, ghosts or otherworldly spirit-harvesters do not alter that a jot. What he’s not is a lumpen naturalist—the reality he depicts contains more things than are dreamt of in our philosophy. But it’s still real, still natural. It is a naturalism invigorated but never overwhelmed by the uncanny.

The most brilliant expression of this comes in “Liar’s House”, the recounting of one of the dragon Griaule’s opaque schemes. There is one throwaway clause, early on, which provides a startling insight into Shepard’s project. Describing his sculptures of the great Griaule, the protagonist Hota sees them as “objects that—like their model—appeared to be natural formations that bore a striking resemblance to dragons.”

Run though that implicit description of Griaule. What does a miles-long, vastly recumbent dragon look like? It looks like a mountain range that looks like a dragon.

Here is an answer to the conundrum, faced whether they acknowledge it or not by all writers of the fantastic, of how to describe the magically indescribable. All we have for reference is the everyday.

With this extraordinary sentence—which must surely go down as one of the most incisive, radical and rigorous examinations of the fantastic in fantasy—Shepard achieves something remarkable. On the one hand, he undercuts the self-big-up of magic. We cast about for similes, but the magic is, and can be, “like” nothing other than the mental furniture we have to hand, that very unmagic stuff all around us.

At the same time, Shepard honours that everyday too often denigrated. What, the analogy asks, can be more extraordinary than a mountain? After all, they are what dragons look like! Dragons, in this radical grammar, aren’t their own end; they are referents to help us visualise rocks. What an astonishing thing to do to the fantastic.

But it is astonishing because we know that dragons are astonishing. And we know that, and Shepard knows it, and the analogy knows it too, though it pretends not to.

So this is no crude rebuke or simplistic reversal of priorities: it is a fractal blossoming of reference and counter-reference, a giddying out- and infolding. Shepard does not invert the mawkish privileging of “magic”: he undercuts the unequal binary itself. We’re too enamoured of hierarchical dyads to give them up tout court. Instead, in that elegant and extraordinary comparison, Shepard makes the distinction self-cannibalising, destabilising.

And he points out that we’ve all been doing this all along. The passage is a canny reversal of one of the most clichéd analogies known to poets of geography: what, after all, does a certain type of mountain range look like but a sleeping dragon? It’s a commonplace for us to so “uncover” the never-very-covered-up-anyway magic under the skin of the natural; here is fantasy that lays bare the natural below the magic.

Lucius Shepard has a name for what he does. In the story notes to “Abimagique”, he memorably describes one of his strengths as a writer as “bungling naturalism”. Read him and you read a naturalist who bungles, repeatedly and almost seemingly inadvertently straying into the unnatural, the supernatural. Fantasy here is a kind of systemic, fecund and felicitous writerly mistake, one that vastly invigorates the naturalism Shepard seemed to be angling for.

“Bungling Naturalism” may the best term for serious non-realist literature ever arrived at. It is a great boon to fiction that Shepard strives for the kind of naturalism he does; and it is a great boon to fantasy that he so brilliantly bungles.

China Miéville

FOR

BOB AND KAROL

STARS SEEN THROUGH STONE

I was smoking a joint on the steps of the public library when a cold wind blew in from no cardinal point, but from the top of the night sky, a force of pure perpendicularity that bent the sparsely leaved boughs of the old alder shadowing the steps straight down toward the earth, as if a gigantic someone above were pursing his lips and aiming a long breath directly at the ground. For the duration of that gust, fifteen or twenty seconds, my hair did not flutter but was pressed flat to the crown of my head and the leaves and grass and weeds on the lawn also lay flat. The phenomenon had a distinct border—leaves drifted along the sidewalk, testifying that a less forceful, more fitful wind presided beyond the perimeter of the lawn. No one else appeared to notice. The library, a blunt Nineteenth Century relic of undressed stone, was not a popular point of assembly at any time of day, and the sole potential witness apart from myself was an elderly gentleman who was hurrying toward McGuigan’s Tavern at a pace that implied a severe alcohol dependency. This happened seven months prior to the events central to this story, but I offer it to suggest that a good deal of strangeness goes unmarked by the world (at least by the populace of Black William, Pennsylvania), and, when taken in sum, such occurrences may be evidence that strangeness is visited upon us with some regularity and we only notice its extremes.

Ten years ago, following my wife’s graduation from Princeton Law, we set forth in our decrepit Volvo, heading for northern California, where we hoped to establish a community of sorts with friends who had moved to that region the previous year. We elected to drive on blue highways for their scenic value and chose a route that ran through Pennsylvania’s Bittersmith Hills, knuckled chunks of coal and granite, forested with leafless oaks and butternut, ash and elder, that—under heavy snow and threatening skies—composed an ominous prelude to the smoking red-brick town nestled in their heart. As we approached Black William, the Volvo began to rattle, the engine died, and we coasted to a stop on a curve overlooking a forbidding vista: row houses the color of dried blood huddled together along the wend of a sluggish, dark river (the Polozny), visible through a pall of gray smoke that settled from the chimneys of a sprawling prisonlike edifice—also of brick—on the opposite shore. The Volvo proved to be a total loss. Since our funds were limited, we had no recourse other than to find temporary housing and take jobs so as to pay for a new car in which to continue our trip. Andrea, whose specialty was labor law, caught on with a firm involved in fighting for the rights of embattled steelworkers. I hired on at the mill, where I encountered three part-time musicians lacking a singer. This led to that, that to this, Andrea and I grew apart in our obsessions, had affairs, divorced, and, before we realized it, the better part of a decade had rolled past. Though initially I felt trapped in an ugly, dying town, over the years I had developed an honest affection for Black William and its citizens, among whom I came to number myself.

After a brief and perhaps illusory flirtation with fame and fortune, my band broke up, but I managed to build a home recording studio during its existence and this became the foundation of a career. I landed a small business grant and began to record local bands on my own label, Soul Kiss Records. Most of the CDs I released did poorly, but in my third year of operation, one of my projects, a metal group calling themselves Meanderthal, achieved a regional celebrity and I sold management rights and the masters for their first two albums to a major label. This success gave me a degree of visibility and my post office box was flooded with demos from bands all over the country. Over the next six years I released a string of minor successes and acquired an industry-wide reputation of having an eye for talent. It had been my immersion in the music business that triggered the events leading to my divorce and, while Andrea was happy for me, I think it galled her that I had exceeded her low expectations. After a cooling-off period, we had become contentious friends and whenever we met for drinks or lunch, sh

e would offer deprecating comments about the social value of my enterprise, and about my girlfriend, Mia, who was nine years younger than I, heavily tattooed, and—in Andrea’s words—dressed “like a color-blind dominatrix.”

“You’ve got some work to do, Vernon,” she said once. “You know, on the taste thing? It’s like you traded me in for a Pinto with flames painted on the hood.”

I stopped myself from replying that it wasn’t me who had done the trading in. I understood her comments arose from the fact that she had regrets and that she was angry at herself: Andrea was an altruist and the notion that her renewed interest in me might be partially inspired by envy or venality caused her to doubt her moral legitimacy. She was attractive, witty, slender, with auburn hair and patrician features and a forthright poise that caused men in bars, watching her pass, to describe her as “classy.” Older and wiser, able by virtue of the self-confidence I had gained, to cope with her sharp tongue, I had my own regrets; but I thought we had moved past the point at which a reconciliation was possible and refrained from giving them voice.

In late summer of the year when the wind blew straight down, I listened to a demo sent me by one Joseph Stanky of Mckeesport, Pennsylvania. Stanky billed himself as Local Profitt Jr. and his music, post-modern deconstructed blues sung in a gravelly, powerful baritone, struck me as having cult potential. I called his house that afternoon and was told by his mother that “Joey’s sleeping.” That night, around 3 AM, Stanky returned my call. Being accustomed to the tactless ways of musicians, I set aside my annoyance and said I was interested in recording him. In the course of our conversation, Stanky told me he was twenty-six, virtually penniless, and lived in his mother’s basement, maintaining throughout a churlish tone that dimmed my enthusiasm. Nevertheless, I offered to pay his bus fare to Black William and to put him up during the recording process. Two days later, when he stepped off a bus at the Trailways station, my enthusiasm dimmed further. A more unprepossessing human would be difficult to imagine. He was short, pudgy, with skin the color of a new potato and so slump-shouldered that for a moment I thought he might be deformed. Stringy brown hair provided an unsightly frame for a doughy face with a bulging forehead and a wispy soul patch. His white T-shirt was spattered with food stains, a Jackson Pollack work-in-progress; the collar of his windbreaker was stiff with grime. Baggy chinos and a trucker wallet completed his ensemble. I knew this gnomish figure must be Stanky, but didn’t approach until I saw him claim two guitar cases from the luggage compartment. When I introduced myself, instead of expressing gratitude or pleasure, he put on a pitiful expression and said in a wheedling manner, “Can you spot me some bucks for cigarettes, man? I ran out during the ride.”

Vacancy & Ariel

Vacancy & Ariel The Dragon Griaule

The Dragon Griaule The Ends of the Earth

The Ends of the Earth Two Trains Running

Two Trains Running Life of Buddha

Life of Buddha Louisiana Breakdown

Louisiana Breakdown AZTECHS

AZTECHS Life During Wartime

Life During Wartime Green Eyes

Green Eyes Beautiful Blood

Beautiful Blood Stars Seen Through Stone

Stars Seen Through Stone Viator

Viator Colonel Rutherford's Colt

Colonel Rutherford's Colt Dagger Key and Other Stories

Dagger Key and Other Stories Eternity and Other Stories

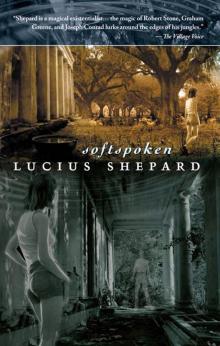

Eternity and Other Stories Softspoken

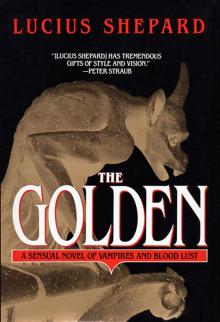

Softspoken The Golden

The Golden