- Home

- Lucius Shepard

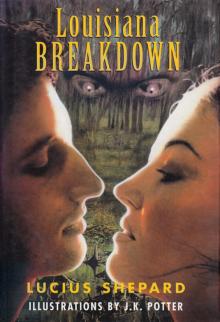

Louisiana Breakdown

Louisiana Breakdown Read online

WHEN THE GOOD GRAY MAN

COMES CALLIN’…

Welcome to Grail, Louisiana!

A little hole of a town near the Gulf—next to nothing and just beyond reality—where hoodoo meets Jesus and the townsfolk pray to them all.

When there ain’t nowhere else to be in Grail, you’ll find folks at Miss Sedele’s bar, Le Bon Chance—dancin’, shootin’ dice, knockin’ back beers and those weird green drinks she’ll mix up for you called “cryptoverdes.” The Chance is the kind of place you just might get lucky in…

Then there’s Vida Dumars. She’s the Midsummer Queen, but her reign ends tomorrow evening. Vida’s got the kind of body that turns heads and makes a guy’s jaw drop, wishin’ he could get himself a piece of that. Vida owns the Moonlight Diner, but she’s a strange one. Scares people even. Why she can see right through you, into your deepest heart, as if…well, as if you was a picture window. But Vida’s got her own secrets—down deep, dark secrets.

And a new guy arrived in town today, name of Jack Mustaine. His BMW broke down and now he’s stuck in Grail for a few days. Jack’s one of those singer-songwriters from L.A.; he can bend the strings on that steel guitar and make music that damn near wrenches the soul right outta your gut. But Jack’s a man on the run—though whether he’s running from somethin’ or running to somethin’ even he don’t rightly know. Jack hooked up with Vida at Le Bon Chance this evening, so sparks are sure to fly. Vida seen a strength in Jack that even he don’t know he got, but is he strong enough to stand against what he and Vida will face in the next twenty-four hours?

You see, a coupla hundred years ago, the founders of Grail made a deal with somebody they called the Good Gray Man. Some kinda spirit that’s supposed to be hangin’ around these parts. He promised good fortune to the town so long as they kept up the tradition of the Midsummer Queen. So every twenty years, on Midsummer Night’s Eve, the town chooses a ten-year-old girl to be the new Queen. She’s the luck o’ the town. She draws all the bad luck to her so’s Grail can prosper. And tomorrow Vida Dumars passes her scepter to the new Midsummer Queen. Tomorrow Vida will no longer be the luck o’ the town. Tomorrow the Good Gray Man comes callin’…

Author Lucius Shepard uses the trappings of the dark fantasy story to delve into the psychological and motivational depths of his characters, including the town of Grail itself. Novella Louisiana Breakdown reveals the author at the peak of his writing prowess—a tour de force of character, imagery, and tone. With a Foreword by New Orleans author Poppy Z. Brite, and an Afterword, interior illustrations, and endpapers by New Orleans artist J. K. Potter.

Praise for the author’s previous novel, Valentine:

“Shepard’s novel is haunting and magical…[his] protagonist intersperses the passionate entreaties of a man in love with philosophical musings on memory, desire, chaos, synchronicity, fate, and the way that different stories play out in our lives.”

—Booklist

Copyright © 2003 by Lucius Shepard

Foreword copyright © 2003 by Poppy Z. Brite

Afterword copyright © 2003 by J. K. Potter

Illustrations copyright © 2003 by J. K. Potter

Edited by Marty Halpern

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Shepard, Lucius.

Louisiana breakdown / by Lucius Shepard; with a foreword by Poppy Z. Brite; and an afterword and interior illustrations by J. K. Potter.—1st ed.

p. cm.

ISBN 1-930846-14-2 (hardcover: alk. paper)

1. Louisiana—Fiction. 2. Summer solstice—Fiction. 3. Festivals—Fiction. 4. Queens—Fiction. I. Title.

PS3569.H3939 L68 2003

813’.54—dc21

2002014587

All rights reserved, which includes the right to reproduce this book, or portions thereof, in any form whatsoever except as provided by the U.S. Copyright Law. For information address Golden Gryphon Press, 3002 Perkins Road, Urbana, IL 61802.

Printed in the United States of America.

First Edition

Contents

Foreword

Poppy Z. Brite

Louisiana Breakdown

Afterword

J. K. Potter

To Mark and Nancy Jacobson

Foreword

I AM NOT CERTAIN WHY I HAVE BEEN ASKED TO WRITE this introduction, since Lucius Shepard was publishing great stories like “Delta Sly Honey” in Twilight Zone when I was a pup with no credentials whatsoever. It’s rather like Barry Whitwam, the drummer of Herman’s Hermits, being asked to introduce this great new album Rubber Soul. You don’t need me to hype Lucius to you, but since I’m here, I’ll attempt to say a few semicogent things about Louisiana Breakdown before letting you get to it.

A local friend and I have recently been making fun of most fiction set in New Orleans and the rest of south Louisiana—two distinct environs frequently confused by writers who populate the French Quarter with Cajuns and drop Marie Laveau off somewhere near Lafayette. He e-mailed me about a day in the life of a typical New Orleans character: “Wake up in an unairconditioned, dimly lit room (or houseboat on ‘the bayou,’ wherever the fuck that is), light a cigarette, blow smoke into the ceiling fan and gripe to yourself about the stifling heat…” I wrote back to describe a mystery novel I’d read in which the heroine fell off a wrought-iron balcony and landed in a giant king cake, and I concluded the e-mail, “Hang on, Boudreaux’s at the door. We’re going to the Mardi Gras parade. Hope he brought me a nice sack of crawfish.”

You live in a fairy tale, you get bombarded with clichés. In south Louisiana, one of our pitiful defenses against this is to mock ourselves more readily and viciously than any outsider can, congratulating ourselves on the quaintness of our corrupt politicians and bragging about being the murder capital of America (I believe New Orleans earned that dubious distinction in 1993). As Miss Sedele Monroe, a character in Louisiana Breakdown, points out, “New York, Los Angeles…Omaha, you look beneath the surface, it’s nuts everywhere. Difference ’tween the rest of the world and Grail, our surface been peeled away for a couple hundred years. We in what’cha might call plain fuckin’ view.”

Which just goes to show that another, better defense is to write honestly about the place, but that’s difficult to do. I’ve been writing about it since 1986 and haven’t acquitted myself yet. I usually tell people that John Kennedy Toole’s A Confederacy of Dunces is the only honest book ever written about New Orleans. In truth, there’s a handful of fiction that manages to plumb the region’s magic without drowning in the clichés. Louisiana Breakdown is such a piece.

In particular, Lucius Shepard captures the south Louisiana sense of pantheism better than any other author I’ve read. The Native American gods became swamp monsters, the Catholic saints merged bloodily with the Creole voodoo pantheon, the Old Ones stopped by a storefront church on Claiborne Avenue, and we still pray to any and all of them according to what seems most efficacious. Some of these characters understand that, some are snared by it unsuspecting, but all are affected. Imagine this told in Lucius’s lyrical-badass voice, like some hybrid of Orpheus and Tom Waits talking about “white ribbon tied around a cypress trunk” and “this chicory-flavored nowhere” and Vietnamese neon characters seen through mist, and you’ll have Louisiana Breakdown. Go on now—and enjoy your vacation in Grail. You won’t really understand it unless you’re from there, but it will change you, and that is the most important thing we can ask of travel.

Poppy Z. Brite

New Orleans

July 2002

Louisiana

Breakdown

1

June 22

YOU EVER HEAR ABOUT THIS LITTLE PLACE DOWN IN Louisiana, this nowhere town o

n the Gulf name of Grail? Got a sugar refinery what’s been shut down, waters are near fished out. Scrawny old suspender-wearing men listening to baseball on the gas station radio, spitting Red Man and staring at the license plates of cars that burn past without even slowing, on their way to somewhere better, though the old men wouldn’t never admit it. Business district is a couple of blocks of Monroe Street. Shops in three-story buildings of friable brick that were new in turn-of-the-century photographs. Faded advertisements painted on the walls portraying sewing machines and refrigerators and shoes from the 1930s, the windows so dusty, God only knows what’s sold inside. Dinged cars and battered pickups parked on the slant with gray patches of Bondo on their fenders, Ragin’ Cajun decals polka-dotting the windshields. Bait store, grain store, convenience store, all faced with white plastic panels, and signs on the poles outside with misspelled words in black stick-on letters and prices with the numbers hanging cockeyed.

Fishing boats moored at a weathered pier that juts out into a notch of the Gulf, every metal surface scabbed with rust, grimy blue rag tied like a tourniquet around a broken mast.

Creosote smell from the pilings.

Brine and gasoline.

A pelican with spread wings perched on an oil drum.

There’s enough bars to keep a town twice the size drunk forever, and more than enough drunks to keep them busy. Cross streets with aluminum-sided houses, some smaller than the tombs you find in St. Louis Number Two graveyard back in New Orleans. Elementary school named for a football player. The Assembly of God Church looks like a white army barracks and, separated from it by a neat green lawn, St. Jude’s is a frame structure with a clapboard steeple that looks as if it should be New England Episcopal and not Roman Catholic. Churchgoers will pile out of the doors, mingle on the lawn, a syncretism of hellfire shouters and mystical animists. Florid men in plaid jackets, white belts, and pastel slacks talking real estate and golf with leaner men wearing Elvis Presley sideburns and black suits. Wives smile and clutch purses to their waists. Sunday thoughts slide like swaths of gingham through their minds.

Beyond the brick buildings, the businesses thin out along Monroe, weedy vacant lots between them, palmettos fountaining up, hibiscus bushes and a few scrub oaks, the ground littered with beer cans and condoms and yellowed newspapers.

Crosson’s Hardware, where you can purchase any kind of firepower, lay bets, join the Klan.

Joe Dill Realty, Joe Dill Brokerage, Joe Dill Construction, all occupying the Dill Building, along with a dentist, a doctor, an accountant, the town ambulance chaser.

Police station, barbershop, Whitney Bank.

A boarded-up arcade, a little concrete box postage-stamped to infinity with posters and placards advertising revivals, carnivals, failed politicians.

Dairy Queen.

Nights, kids sit on stone benches out front, in the spill of glare from the cash window, sipping milk shakes, licking that soft ice cream with the curlicue on top, while others cruise in a tight circle around the building, gunning their engines, the radios up loud. Kids from Grail High, the Grail Crusaders. Basketball team made it to the state semis this year, and everybody was real proud. Watching from a distance, you have the idea that something more than what’s apparent must be going on, that it’s a Norman Rockwell nightmare. Like the kids are programmed by some hellish force, they’re speaking Latin backwards, they’re on the lookout for enemies of Satan. Black silhouettes shading their eyes against headlights, peering to see who’s riding in the cars. A couple starts dancing to heavy metal on a boom box. Moths whirling above their heads are the souls of the damned.

Police cruiser idles, rumbling on the corner opposite, a ruby cigarette coal glowing behind the windshield.

Screams, wild laughter, glass breaking.

Two shadows stepping fast past Louisianne Hair Boutique, Dill’s Liquors, Jolly’s Lumber.

In the window of Cutler’s Lawn and Garden there’s a huge poster showing shiny red tractors and green cultivators and yellow riding mowers trundling over a section of perfect farmland, like an opening into a better world.

THIS IS JOHN DEERE COUNTRY reads the banner above it.

The Gulfview Motel is six pink stucco cabins with peaked roofs and a plaster birdbath next to the office. Across the street, Club Le Bon Chance, a low concrete block building with electric Dixie Beer ads tattooing the black windows, and a neon sign shaped like a pair of dice that tumble a ways over the rooftop and change from showing a four and a three to snake eyes. The parking lot’s never empty, the music never ends. Miss Sedele Monroe grows older at the end barstool every day from two P.M. until something intriguing comes along, soothing her redheaded soul with mysterious elixirs. Her life’s a scarlet rumor. They say you ain’t lived ’til she’s doctored your Charlie, but just don’t go and let that green left eye of hers lock onto yours.

Presley’s original drummer, D. J. Fontana, plays at the club now and then. Talks about barnstorming through Louisiana in a pink Cadillac. How the women were, how the rednecks wanted to cut them. People come from all over, stare at him like he’s a holy relic. He’s so old, they say with fond, delicate amazement. He’s so old.

Two men killed recently, one knifed beside the pool table, the other beaten to death in the john.

Charlotte Slidell of Golden Harvest, 23, was last seen dancing there one April night two years ago.

This time of year, it always seems hotter after dark.

Sunsets are terrific here. There’s no work to be had, but patriotism runs high. They say it’s a great place to raise kids. Solid values, clean air. The kids can’t wait to leave. You might wonder why anyone would want to stay in a place like this, a place that has about as much purpose as a fly buzzing around something that ain’t fit to eat. What keeps them going year after year through boredom and welfare hassles, hurricanes and heat? Belief, that’s the answer. Not belief in God necessarily, nor in America. Nothing that simple. These people have a talent for belief. They’ve learned to believe in whatever’s necessary to preserve the illusion of the moment. They’ll tell you stories about the Swamp Child, about the Kingdom of the Good Gray Man, about voodoo and hoodoo and how you can do it to whoever you want long as you got the coin to pay the old Nanigo woman who lives in the mangrove where mosquitoes whine and gators belly-flop into the black water. Jesus Lives. So does Shango, Erzulie, Damballa, half a dozen others. Plastic Virgin tacked to a wall, with paper hearts and broken scissors and a wristband of goat hair on the altar beneath. White ribbon tied around a cypress trunk. One hundred red candles burning on a porch. The believers softly breathe. Whisper the words. They smile, they nod. The mystic is here. Ineffable voices are heard. The anonymous saints of endurance manifest. This is the one true home. They don’t care if you believe it. They know, they know. Strangers can’t understand the secrets they control.

Miss Nedra Hawes, Oracles and Psychic Divination.

Crescents and ankhs and seven-pointed stars.

With a noise like birdshot ripping through leaves, a sudden gust drives grit against the windows of Vida’s Moonlight Diner, a railroad car painted white and decorated all over with groupings of brightly colored lines. Veves. Voodoo sign.

Past the diner, on the eastern edge of town, a dirt road lined with shotgun cabins leads off toward the Gulf. Shotgun Row. That’s where the blacks live, some poor whites, other outcasts, the cabins blended in with cypress, live oaks, swamp. Past the dirt road, past the city limits and the dump, past the winding asphalt road that leads to the development where most of the solid citizens live, there’s a trail barely noticeable from the highway. A footpath choked by chicory bushes, wild indigo, ferns. No one ever goes there, no offerings are left to appease or placate. Children are not warned away. It’s not evil, it’s simply a forgotten place, or else a place people want to forget. Standing there, watching grackles hopping in the high branches of an oak, slants of paling dust-hung light touching the tops of the bushes, listening to chirrs and p’weets and frogs ratchetin

g, you get the feeling that something’s living out in the shadows, out with the two-headed lizards and the albino frogs, all the mutant things of pollution, something big and heavy and slow and sad, not a threat to anything but itself, something that wanders through the green shade, lost and muttering, peeking between the leaves, ducking whenever a car passes, scurrying back to its hole. There’s a secret here, a powerful secret. An old tension in the air. But who controls it, who does it control? That’s a secret nobody wants to know.

Ribbon of dark water veining into the swamp beyond.

Wind makes a river, the trees make a moan.

Spider web trembles, but the spider ain’t home. Moonlight slips like a silver fluid down the strands, the whole structure belling, the strange silky skeleton woven of a life through time, fragile yet resilient for all its frays, beautiful despite the husks of recent victims and the unconsumed legs of a dead lover.

The baseball game has ended. The old men are tucking their tobacco pouches away, getting ready to go home. One slaps the radio in disgust. It takes some of them two, three tries to heave up from their chairs. Down at the pier, Joe Dill, a muscular black-haired man in jeans and a blue work shirt steps from the cabin of a fishing boat, flings down a wrench and looking up, says “Shit!” to the sky. The parking lot behind the Dill Building is emptying, the cars heading east out of town, some pulling into Club Le Bon Chance. A string of pelicans crosses the breakwater, flapping, then gliding, spelling out a sentence of cryptic black syllables against the overcast. A crane steps with Egyptian poise through scummy shallows. Sandpipers scuttle along a ragged strip of tawny beach west of the pier. Potbellied, their heads tipped back, they stop and pose like pompous little professors. Candy-flake red Camaro Z-28 lays rubber down Monroe, and a bald man who’s locking up a shop in one of the brick buildings scowls and shakes his head. A frail, wrinkled lady in a lace-collared dress tapping with her cane along the sidewalk, heading back from Dill’s Liquors, her shopping bag heavy with a week’s supply of vodka. Two teenage girls sneaking a joint in the alley between the arcade and the bank watch her pass with somber expressions, and once she’s out of sight they exchange glances and break out in giggles.

Vacancy & Ariel

Vacancy & Ariel The Dragon Griaule

The Dragon Griaule The Ends of the Earth

The Ends of the Earth Two Trains Running

Two Trains Running Life of Buddha

Life of Buddha Louisiana Breakdown

Louisiana Breakdown AZTECHS

AZTECHS Life During Wartime

Life During Wartime Green Eyes

Green Eyes Beautiful Blood

Beautiful Blood Stars Seen Through Stone

Stars Seen Through Stone Viator

Viator Colonel Rutherford's Colt

Colonel Rutherford's Colt Dagger Key and Other Stories

Dagger Key and Other Stories Eternity and Other Stories

Eternity and Other Stories Softspoken

Softspoken The Golden

The Golden