- Home

- Lucius Shepard

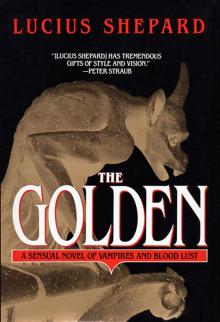

The Golden

The Golden Read online

An evocative,

unforgettable novel of

vampires and blood lust…

THE

GOLDEN

by Lucius Shepard

They are the Family. They are vampires. And they have gathered at Castle Banat to savor one they call the Golden, a mortal whose bloodlines reflect more than three centuries of careful, patient breeding.

Now that the wait is over at last, they have come from all across Europe for the Decanting, eager to drink the exquisite, long anticipated elixir. But what should be one of the Family’s finest moments is snatched from them. For someone ruthlessly murders the Golden, ravaging her body to drain every last drop of precious blood…and robbing her of the immortality—the change from life to life—that would have been hers.

The task of hunting down the killer falls to Michel Beheim, former chief of detectives in the Paris police force. A mere child among the Family, only two years a Vampire compared to the centuries many others claim, Beheim believes he will be able to solve this murder as he solved those of his former life. But the motivations, the actions—the very concept of evil—are quite different for vampires than for ordinary mortals.

It is the Lady Alexandra who first demonstrates just how dangerous Beheim’s lack of experience may prove when she comes to his apartments to offer a clue, or rather, a hint of evidence. Both the murder and his investigation are part of a greater game, she says. Then—as cruel as she is seductive—she warns her new chosen lover that he should make no assumptions with regard to the players’ ultimate goals…not even her own.

So Beheim enters the game, following a twisting trail that leads from Alexandra’s arms into the terrifying nightmare depths of Castle Banat…to a hidden chamber that holds secrets even the Family cannot fathom…to the lairs of centuries-old vampires possessed of knowledge and powers far beyond his own. And, in the midst of his fear and new hungers, Michel Beheim discovers that his professional skills alone cannot save him from those who would condemn him to an eternal hell, or from the unfathomable, growing darkness in his own immortal soul.

Books by Lucius Shepard

Novels

THE GOLDEN

LIFE DURING WARTIME

GREEN EYES

Short Fiction

THE JAGUAR HUNTER

THE ENDS OF THE EARTH

THE GOLDEN

A Bantam Book

All rights reserved.

Copyright © 1993 by Lucius Shepard.

Cover photo copyright © 1993 by Marbury/Art Resource, NY.

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or

mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval

system, without permission in writing from the publisher. For information address:

Bantam Books.

ISBN 0-553-56303-3

Published simultaneously in the United States and Canada

* * *

Bantam Books are published by Bantam Books, a division of Bantam Doubleday Dell Publishing Group, Inc. Its trademark, consisting of the words “Bantam Books” and the portrayal of a rooster, is Registered in U.S. Patent and Trademark Office and in other countries. Marca Registrada. Bantam Books, 1540 Broadway, New York, New York 10036.

* * *

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

For Michael and Mary Rita

I’m very grateful to the following people for their assistance during the making of this book: Jim Turner, Ralph Vicinanza, Chris Lotts, Robert Frazier, Mark and Cindy Ziesing, Arne Fenner, and Jennifer Hershey.

Contents

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter ONE

The gathering at Castle Banat on the evening of Friday, October 16, 186–, had been more than three centuries in the planning, though only a marginal effort had been directed toward the ceremonial essentials of the affair, its pomp and splendor. No, most of that time and energy had been devoted to the nurturing and blending of certain mortal bloodlines so as to produce that rarest of essences, a vintage of unsurpassing flavor and bouquet: the Golden. Members of the Family had come from every corner of Europe to participate in the Decanting, traveling at night by carriage or train and stopping at country inns during the day. Now, clad in their finest gowns and evening dress, some accompanied by mortal servants, who—though beautiful and well dressed in their own right—seemed by contrast like those drab ponies chosen to lead Thoroughbreds onto a race course, they mingled in the ballroom, a cavernous vault of mossy stones supported by flying buttresses, lit by dozens of silver candelabra, and dominated by a fireplace large enough to roast a bear. Among the gathering were representatives of the de Czege and Valea branches, who were currently embroiled in a territorial dispute; yet tonight this and other similar disagreements had been set aside and an uneasy truce installed. There was laughter, there was clever conversation, there was dancing, and it looked for all the world as if it were the kings and queens of a hundred nations who had assembled to celebrate some splendid royal function, and not a convocation of vampires.

Yet despite the gaiety of the assemblage, not every conversation was free from bitterness. Standing by a corner of the fireplace, their faces ruddied by the light, two men and a woman were discussing a topic of some controversy: the proposal that the Family bow to the pressures currently being applied by its enemies and relocate to the Far East, where their activities would be more difficult to detect due to the primitive conditions and the forbidding, often unexplored terrain. Championing the proposal was the elder of the men, Roland Agenor, the founder of the Agenor branch, whose position as the chronicler and historian of the Family gave added weight to his opinions. Tall, patrician, with a luxuriant growth of white hair, he had the bearing of a retired officer or an accomplished athlete come to a graceful maturity. Opposing him in the discussion was the Lady Dolores Cascarin y Ribera, a dark-skinned beauty with waist-length black hair and a predatory voluptuousness of feature. She had become the de facto spokesman for the more reactionary elements of the Family, those who maintained that no quarter be asked or given in the struggle, an attitude that embodied the Family’s traditional disdain toward all mortals. The third member of the group, Michel Beheim, was a lean young man, taller even than Agenor, with curly brown hair and remarkable large dark eyes that lent his face an almost feminine delicacy and ardor and supported the impression that he was always on the verge of bursting forth with some heated opinion…though at the moment he felt entirely at sea. As Agenor’s protégé he was compelled to lend his support to the historian, yet being among the newest—and thus the weakest—of the Family’s initiates, having received his blood judgment less than two years previously, he could not help but be swayed by Lady Dolores’s beauty and passion, by the flamboyant and seductive potency of the tradition whose spirit she expressed. He found himself nodding by reflex at her telling points and staring at the dusky swell of her breasts, at the cruel, ripe curves of her mouth, and imagined the two of them together in a variety of erotic postures. So distracted was he by her physical presence that when Agenor exhorted him to respond to one of the lady’s assertions, he was forced to admit that he had lost track of her argument.

Agenor regarded him with disfavor, and Lady Dolores laughed contemptuously. “I doubt he would have

anything of consequence to offer, Roland,” she said.

“Your pardon—” Beheim began, but Agenor cut him off.

“My young friend may be new to us,” he said, “but let me assure you, he is most astute. Did you know that prior to his judgment he achieved the position of chief of detectives in the Paris police? The youngest, I believe, ever to reach such heights.”

Lady Dolores made a deferential gesture. “Nothing in a policeman’s experience can have the least bearing upon the subject of our debate.”

This time it was Beheim who cut off Agenor when he began to speak.

“With respect, my lady, it demands neither a wealth of experience nor any great art of reason to deduce that changes are in the offing. For the world…and for the Family. To espouse a doctrine of death before dishonor is scarcely wise, especially when one considers that by doing so one forfeits all further opportunities for honorable accomplishment.”

“You do not yet hear the song of your blood,” said Lady Dolores. “That much is apparent.”

“Oh, but I do!” Beheim returned, though uncertain whether she was referring to something actual or merely waxing metaphorical. “And your arguments have gone far in enlisting my pride, my sense of honor. But pride and honor, too, must confront the realities or else they become mere conceits. As you well know, certain medicines have been developed that allow us to forgo the dark sleep and other of the colorful hindrances long attendant upon our condition, and thus we may pass the daylight hours in whatever occupation we favor…so long as we keep from the light. And the time draws near when our men of science, perhaps one who even now labors in my lord’s service”—he nodded to Agenor—“will devise a means by which we may walk abroad in the day. This is an inevitability. And with that change, must not everything about us change? I think so. We will be forced to redefine our role in the affairs of the world. I suspect we will someday redefine as well our stance toward mortal men and join with them in great enterprises. Perhaps never wholeheartedly, perhaps never openly as regards who and what we are. But at least to some degree.”

“The idea of walking about in the daylight does not entice me,” said Lady Dolores. “As for joining with mortals in any enterprise other than feeding, I can find no words to express my distaste. Next you will suggest that we seek counsel from the cattle in the fields. That is no less odious a prospect.”

“We were all mortal once, lady.”

“Spoken like Agenor’s man.”

“I am my own man,” Beheim said sharply. “Should you require proof of this, I will be delighted to supply it.”

First anger, then bemusement washed across Lady Dolores’s face. “Insolence can be an entertaining quality,” she said. “But beware. It will not always find so kindly a reception.”

Her eyes, slightly widened and fixed upon Beheim, went a shade darker, a degree more lustrous, seeming both to menace and to offer sexual promise. A thrill passed across the muscles of Beheim’s shoulders, and it was as if he had grown suddenly small and feeble, diminished by the focus of a vast disapproving majority; yet he recognized this to be merely a consequence of Lady Dolores’s stare. He could feel in it all the weight of her years—two hundred and ninety, so it was said—and the chill potential of her accumulated power. He was helpless before her, like a bird mesmerized by a serpent. Terrified by fate, yet at the same time seduced by it. Her face and form seemed warped, as it might in a watery reflection, and the ballroom itself also looked distorted, areas of darkness expanded, candle flames drawn into flickering, fiery daggers, the entire perspective become that of a fever dream, shadowy avenues leading away between groups of elongated, elegant phantoms who appeared to have stepped out of a nightmare by El Greco. And then, as swiftly as he had been overwhelmed by this feeling, he was free of it, so completely free that he felt for a moment bereft, unsupported, like a child who wakes in the middle of the night to find that he has kicked off the blankets that have been overheating him and causing bad dreams.

“What your scenario fails to take into account,” Lady Dolores said, continuing as if nothing had happened, “is the lustful imprint of our natures, our need to possess and dominate.”

Beheim, still disoriented, had difficulty in marshaling his thoughts, but the goad of Lady Dolores’s haughty expression inspired him to recover.

“I discount nothing,” he said. “Nor will I deny my nature. I am of the Family now and would not wish this to change. However, I choose to interpret our essential condition in a different light than do you. Whereas you insist we have been given a license to exert our will howsoever we desire, a license granted by some anonymous evil pantheon, I submit that we are afflicted with a disease whose most significant symptoms are a craving for human blood and an extended life span. We already have some evidence that this is the case. I’m speaking, of course, of the substance discovered by the Valeas that is manufactured now and again in mortal blood and appears to be a factor in permitting a fortunate few to survive a killing bite and so join with the Family.”

“Extended life span,” she repeated. “Now there’s a meager term with which to describe immortality.”

“You know far more of the Mysteries than I, lady. Yet even you must admit there are doubts regarding the character of this so-called immortality. And therein lies the importance of modifying your view of our condition. If we are to succeed in achieving true immortality and avoiding the grotesque metamorphoses that the centuries bring, we must treat the disease in hopes of ameliorating its long-term effects. If we continue to think of ourselves as grand, erratic masters of the night, volatile lords and ladies who, for all their power and dramatic fever, are tragic, doomed, then we will remain exactly that. While this may satisfy a theatrical urge for self-destruction, it serves nothing else. In my opinion we are, in our excesses of violence and cruelty, less enacting the dictates of our natures than we are indulging the emotions attendant upon an aberrant mentality. We are no longer mortal—this is true. And I have no desire to regain my mortality. Like you, like all of us, I am in love with this fever. Yet I doubt a slight modification of our behaviors would rob us of our natures.”

“You are an infant in these matters,” Lady Dolores said. “Though you speak with passion, it’s clear you are puppet to your master’s thoughts. You may feel something of what I do, but you cannot know the poignancy of those feelings. You have not yet learned the names of the shadows that haunt us.”

“Perhaps not. But it might be said that this is because the symptoms of the disease, the perceptual eccentricities and so forth, are not so well developed in me as they are in you.” Beheim held up a hand to forestall her response. “We could argue this endlessly, lady. Logic is a facile tool, and we can both contrive of it an architecture of deceit. But such is not my aim. This is a matter of interpretation, and I’m only suggesting that you attempt to understand my point of view for the sake of improving our lot. Certainly you’ll agree that holding to traditional views has not won us many battles of late. What harm, then, will it do to consider that there may be another and more promising avenue of possibility?”

Lady Dolores laughed with—Beheim thought—genuine good humor. “With what logical facility you seek to persuade me against the use of facile logic!”

Beheim inclined his head, acknowledging a touch, and was about to press his argument when Agenor glanced at the stairway at the west end of the ballroom, at the massive doors of blackened oak to which it led, and said in a tremulous voice, “She’s here,” a split second before the doors swung open to reveal the figure of a blond girl in a diaphanous nightdress. As she descended the stair, lifting the hem of her garment away from the stones, she brought with her the familiar scent of mortal blood…familiar, yet with a richer, subtler bouquet than any Beheim had ever known. He turned toward her—they all turned—his hunger roused by the delicate actions of that scent. It was so palpable, he imagined it a kind of terrain in which he might wander, a rose garden with a scarlet stream running through it, and the a

ir a numinous golden haze, set swirling by the rhythm of a languorous heartbeat.

The girl made her way among the gathering, all of whom stood stock still as if under a spell. For a mortal she was very beautiful. Slender and pale, her cornsilk hair done up into a coiffure as convulsed as the bloom of an orchid. The creamy swells of her breasts figured by faint traceries of bluish veins. Her eyes—Beheim saw as she drew near, easing past a lanky, hawkish man and his servant—had a mineral intricacy, the irises almost turquoise in color, flecked with topaz and gold, and her upper lip was fuller than the lower, lending her mouth a sensual petulance. The face of a willful child not wholly confident of her sexuality, apprehending yet not quite understanding the power of her body. Beheim was entranced by the swell of her belly, the vulnerability of her breasts in their chiffon nests, and most pertinently by the allure of her blood. His mouth watered; his fingers hooked. He was trembling, he realized, barely able to restrain himself, and overborne by her proximity, he lowered his eyes. If the bouquet of the Golden’s blood could induce such rapturous hunger, he thought, how would it be to taste it?

Once she had passed, he watched her stroll away, walking with an indolent grace such as she might have displayed while taking the air in a park on a summer’s day. The lords and ladies of the Family moved aside, creating a channel that would lead her back to the stairs and thence to the chamber where, under the Patriarch’s protection, she would spend the night and the morrow. But as she was about to pass from sight she interrupted her casual processional and turned to look at Beheim. With a faltering step, she came a few paces back toward him. Her clasped hands twisted at her waist, and she displayed symptoms of arousal: her lips parted, cheeks flushed. Her stare spurred his hunger to new heights. Against reason, his restraint crumbling, he started forward. Yet before he could reach the girl, a hand caught his shoulder and yanked him back. Furious at being thwarted, he spun about, prepared to strike, but the sight of Agenor’s stony face and the force of those luminous black eyes quelled his anger, and he understood what a gross breach of propriety he had committed. As if to second this view, from those standing nearby there arose a surge of whispers and muted laughter. They had been watching him, he realized. All of them. And on spotting the Lady Dolores among the watchers, on registering her triumphant expression, he suspected that she had somehow orchestrated the girl’s arousal—perhaps even his own overwrought reaction—in order to humiliate him. Ablaze with shame, he lunged toward her, but once again Agenor hauled him back, clamping a forearm under his chin and holding him with irresistible strength. The laughter, which had grown briefly uproarious, subsided. The silence that replaced it was freighted with tension.

Vacancy & Ariel

Vacancy & Ariel The Dragon Griaule

The Dragon Griaule The Ends of the Earth

The Ends of the Earth Two Trains Running

Two Trains Running Life of Buddha

Life of Buddha Louisiana Breakdown

Louisiana Breakdown AZTECHS

AZTECHS Life During Wartime

Life During Wartime Green Eyes

Green Eyes Beautiful Blood

Beautiful Blood Stars Seen Through Stone

Stars Seen Through Stone Viator

Viator Colonel Rutherford's Colt

Colonel Rutherford's Colt Dagger Key and Other Stories

Dagger Key and Other Stories Eternity and Other Stories

Eternity and Other Stories Softspoken

Softspoken The Golden

The Golden